The Genius of Mythago Wood

An esotericist's appreciation of Robert Holdstock's classic, unclassifiable novel

Some people still have not read the late Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood, and this makes me sad. Because it’s a profound exploration of the intersections between ancestry, myth, language, consciousness and landscape, masquerading as an accessible, relatively short fantasy novel. I first encountered it as a teenager and took its narrative at face value. Since then, over the years, I’ve re-read it and become progressively enraptured by its hidden depths, because it wears its erudition lightly, yet tackles some of the most complex questions raised by depth psychology.

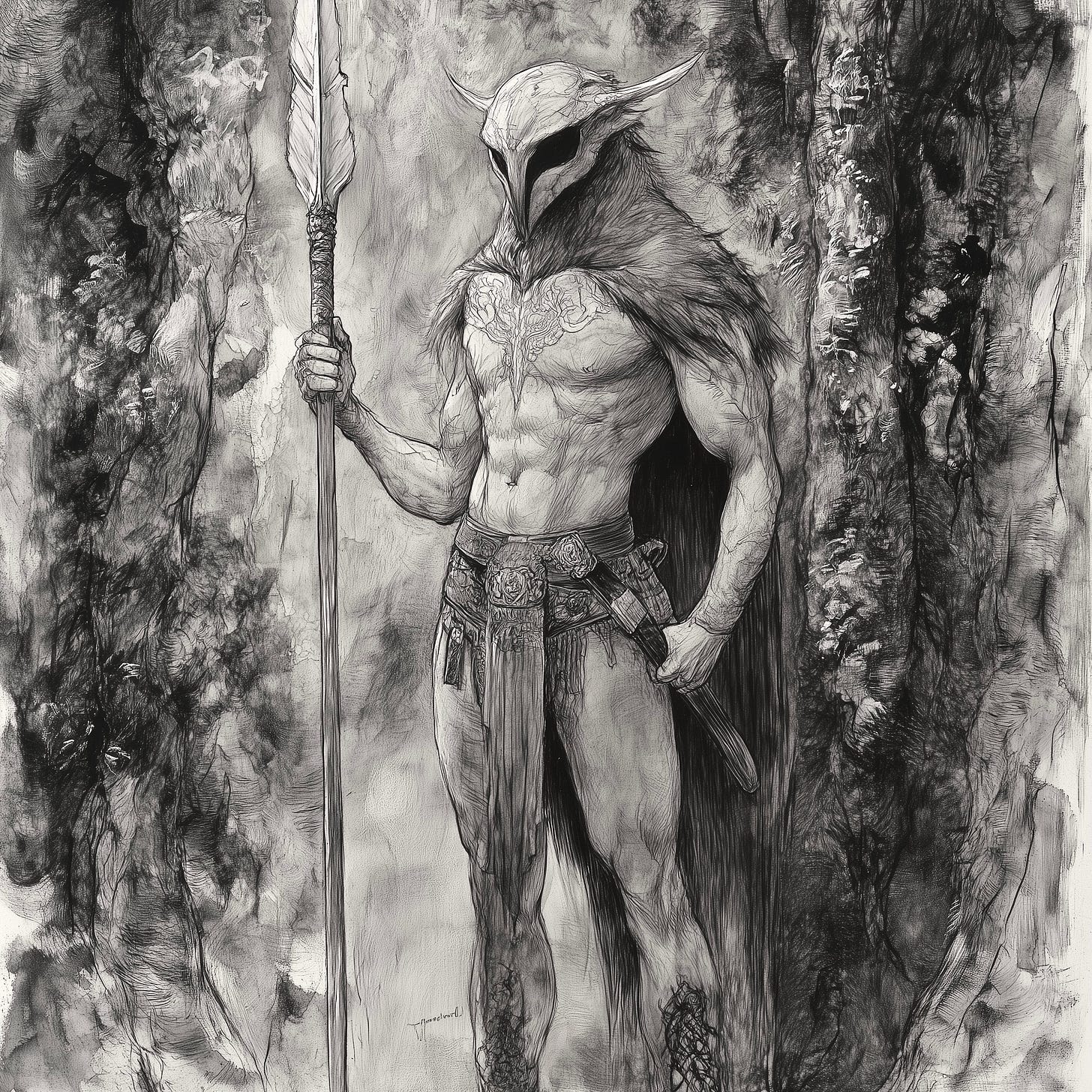

First, a quick plot summary: the novel follows Stephen Huxley, who returns from WWII to his family home, Oak Lodge, adjacent to the enigmatic Ryhope Wood in Herefordshire. His father George, an amateur anthropologist, has died while obsessively studying the wood, and his brother Christopher has become equally consumed by its mysteries. Though apparently only a few square miles when viewed from the outside (or above), the wood encompasses an impossibly vast, primeval landscape where entities called mythagos manifest in physical form. They emerge from the collective unconscious of those who enter the wood, taking the form of archetypal mythic figures from across the strata of human evolution, from Neolithic shamans to English Civil War soldiers. Simultaneously, the wood starts to grow and encroach on the Huxley family home. Stephen and Christopher become obsessed with an Iron Age mythago woman named Guiwenneth, around whom the plot largely revolves. Stephen is drawn into the abyssal heart of the wood in his hunt for Guiwenneth, whom Christian abducts, resulting in a final confrontation and the completion of an unresolved mythic cycle. While the generations of Huxleys bring forth manifestations of mythic archetypes shaped by their individual psychologies, the mythagos possess their own purposiveness and autonomy in conflict with their creators’ will. This is made explicit in the Urscumug - a boar-headed ur-mythago created by George Huxley that functions as a rampaging, primordial steward of the forest. Thus, the book can – on one level – be seen as a parable of personal magickal accountability. But there’s much more to it than that.

The first genius conceit at the heart of the book is Ryhope Wood itself – probably its most important character. In essence the wood is a metaphor for the imaginal; the ‘inner world’ that, through the organ of the active imagination, enables directed engagement with limitless realms and incorporeal intelligences. It is perhaps best understood a dimension intersecting the perceivable, phenomenal world; not an isolated subjective confection but a persistent, collectively accessible ontological reality, albeit epistemologically opaque, and with its own rules and idiosyncrasies. Diverse comparisons have been drawn with: the Celtic otherworld, the astral plane, Plato’s world of Forms1, Karl Popper’s World 3, and the DMT world2. It is in the imaginal that we meet the Jungian archetypes, mythic figures, deities, demons, angels et al. Owen Barfield, the unsung influence on Tolkien, observed that humans are unique in that they exist in the ‘abrupt gap between matter and spirit’3 – a gap that can only be bridged by the imagination.

In common with various depictions of the otherworld, Ryhope Wood is accessible by the physical body; it is porous and bleeds into the world of matter. Once within its borders however, reality becomes stretched and distorted, akin to a dream-state. Like so many journeys into Faerie, time is compressed; a month within the wood equates to a day outside it. Time is also non-linear, inasmuch as myth remains a living, vital force and, through the mythagos, draws the past into the present. Characters refer to the wood as an ‘inner realm’, a place that grows progressively wilder and more primeval the deeper one journeys, metamorphosing according to the psychologies of the protagonists, and the myths of which they are a part. And at the centre of its uncanny geography is a flame-shrouded barrier to the innermost realm (Lavondyss4), recalling the flaming rings and barriers of Norse myth, beyond which lie aspects of the divine feminine.5 Lavondyss can therefore be understood as a location in the wood analogous to the inaccessible primordial wellspring, the point of creation from which all things flow.

The second fascinating aspect of the novel is the way language is used as a metaphor for consciousness, which itself relates to ancestry, lineage and place. The journey to the centre of the wood is a journey through time, the protagonists encountering tribespeople and mythic figures from progressively more remote eras. Close to the innermost realm dwells the mythago known as Sorthalan, a Neolithic shaman, whose ‘language was a sinister series of gutturals and extended diphthongs, a weird and incomprehensible communication that defies even phonetic reproduction.’6

What emerges is a sense of how language shapes human consciousness, which in turn shapes cultural conditions and mythologies; the mythagos emerging from the earliest cultures are the most primal, and also the most powerful and numinous. But their fluidity of appearance and behaviour suggests a connection between linguistic-conceptual development and mythological manifestation. In other words, as human understanding of the world evolves, so too do the forms through which archetypal patterns express themselves.

Returning to Barfield, this philological entanglement with consciousness and culture (and therefore myth) is close to his own theory of words as fossils of human consciousness; linguistic artifacts preserving insights into how earlier peoples experienced and understood reality and, in particular, its spiritual aspects. Holdstock roots these ideas in what he refers to as the ‘racial unconscious’ – the ways in which language, and therefore the means of interpreting reality, mysteriously arise from both place and from the ancestral mind. The words we use and the places in which we use them form a vinculum to the deepest recesses of ancestral memory.7 This lies at the root of indigenous magickal traditions, including the British Mystery Tradition: the acknowledgement that language is a repository for ancient forms of awareness.

The final aspect of the novel, and the one most worthy of attention, is its treatment of myth. In Mythago Wood, myth is not an ossified body of old stories but a dynamic, living force that actively shapes reality, evolving in tandem with human cultural and linguistic development. It is a system that responds to human psychological and spiritual needs – reflecting its utility in ancient / indigenous cultures, and in approaches advocated by Jung.

In entering Ryhope Wood / the imaginal, the Huxleys not only encounter archetypal figures from myth but, through their ancestral links to place, witness those archetypes manifesting in ways that embody and express aspects of their individual psyches. Furthermore, Stephen and Christian become increasingly absorbed into the ever-turning mythic cycles played out in the wood’s inner realms. In this way the novel conveys how all of us exist in a timeline or continuum of mythic activity, where its narratives are yet to be resolved. In the words of Sorthalan the shaman ‘at the moment the story is unfinished’. Yet through our active participation, through our mythopoetic acts, we can write ourselves into mythic narratives. This is, in some respects, the purpose of magick.

Nowhere in the novel is this state of affairs more explicit than in the names of the protagonists. Stephen, the book’s hero, whose name is etymologically linked to ‘crown’, functions as the eternal ‘king’, one of four healthy masculine archetypes according to neo-Jungian Robert Moore.8 Stephen’s brother Christian is the ‘tyrant’, a shadow archetype of the ‘king’. The symbolism of Christian’s name is self-evident: he represents the subjugating, destructive influences of the non-native Abrahamic religion. Their struggle for possession of the mythago woman Guiwenneth can be interpreted as either: a battle for sovereignty over the land, an attempt to exercise control of the feminine principle9, the suppression of spiritual worldviews in favour of materialism, or as a religious conflict between native and invasive systems. The fact that Guiwenneth’s name is cognate with ‘Guinevere’ should clarify matters for the reader.

Mythago Wood really is not a fantasy work, nor is it folk-horror. If anything, it has more in common with so-called ‘magical realism’ and the works of Calvino, Borges, Eco; and especially Alan Garner. It’s a mesmerising, nourishing book that, despite its seemingly inoffensive nature, gets its metaphorical thorns into your skin. It will stay with you, and ask you to re-read it from time to time. Happily, its sequel Lavondyss remains in the same universe, is longer, better-written, gentler, and even more… uncanny.

TBH not a particularly useful comparison as the world of Forms is transcendent and unchanging, whereas the imaginal is malleable and evolving

Given the fact that DMT is highly prevalent in Nature, especially plant life, the DMT world / the imaginal can be said to be part of the Biome, or a function of it

Also the name of the sequel to Mythago Wood

For example, the jötunn Gerðr – emblematic of not just Mother Earth but the female element in general, resides within a flame-ringed sanctuary

Mythago Wood pg 195 (1984 ed)

This is why, in my book Avalon Working, Brythronic is spoken when working in ritual

See ‘King Warrior Magician Lover: Rediscovering the Archetypes of the Mature Masculine’ by Robert Moore and Douglas Gillette.

Really interesting, thank you. By chance I have 'Mythago Wood' earmarked to read for a book group next month. I've not read it before, but am now very keen to get going as this is all right up my street!

Nicely written summary - and goes to the heart of what is so enticing and important about the book. You've made me want to re-read it! Thank you!